But the renminbi’s recent drop below the psychologically significant threshold of ¥7 to the dollar for the first time since 2008 was too much for the Trump administration to take. So, in a symbolic move that escalates America’s ongoing trade war with China, the US Treasury made the official designation.

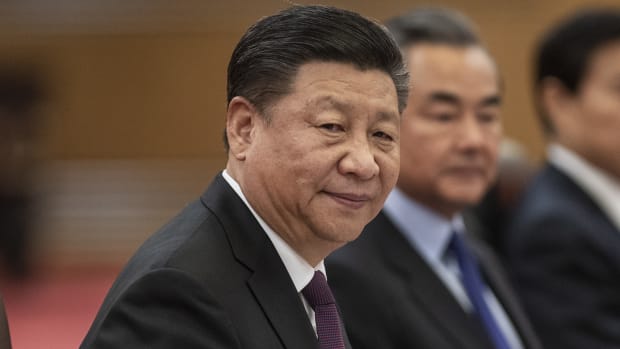

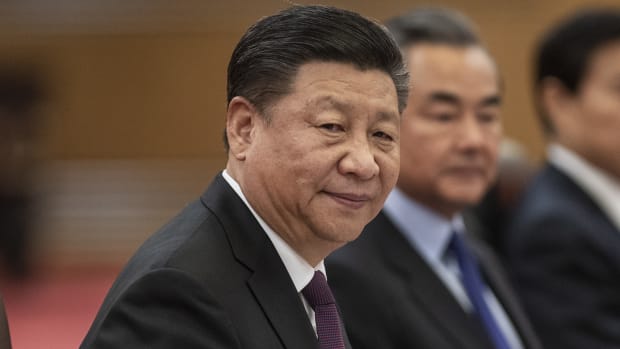

Chinese President Xi Jinping is feeling internal pressure to strike back harder against Donald Trump. AP

It is not at all clear, however, whether the label applies. A country is considered to be a currency manipulator if its monetary authority intervenes to engineer a devaluation, in order to boost the global competitiveness of its exports. The renminbi’s recent decline, however, was not the result of policy action.

Nowadays, China maintains a managed floating exchange rate regime: the renminbi’s value can fluctuate freely within a 2 per cent band. But, because the authorities reset the exchange rate daily, a long period of weakness gradually moves the exchange rate downward, even if daily movements are marginal. That is what happened this week.

In fact, far from intervening to devalue the renminbi, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has in recent years been deploying its foreign exchange reserves to prop it up. The difference this time is that it chose not to intervene, thereby allowing the currency to fall.

The decision was probably driven largely by China’s long-standing determination to transform the renminbi into a major international currency that is liquid and widely accepted. The country’s leaders know that frequent market interventions undermine the renminbi’s credibility with non-resident holders of the currency. Moreover, those interventions come at a high cost. In 2015-16, supporting the renminbi depleted the country’s foreign exchange reserves by some $US1 trillion.

This is not to say that China will not intervene further. After all, a weak currency is a major problem for China – a point that seems to elude the Trump administration. For one thing, by raising the cost of imports, a weaker renminbi would hurt the domestic demand that China is so eager to foster, as part of its strategy to shift the country’s growth model away from exports.

Moreover, a weak renminbi may trigger capital outflows, at a time when total debt stands at a whopping 300 per cent of GDP. A stronger and more stable renminbi, by contrast, would mitigate the debt exposure of Chinese companies and provincial governments, without jeopardising financial stability.

Given this, the PBOC is likely to step in if the renminbi falls much lower. But it will be doing so on its own terms rather than to meet a specified target, let alone to please the US, which would nonetheless benefit. In the throes of Trump’s trade war, and following an interest rate cut by the Federal Reserve, the US could use any growth boost it can get.

Yet, even if China’s interventions are designed to curb depreciation, the Trump administration may nonetheless use them to justify the currency manipulator designation. This points to the dilemma Trump has created for the rest of the world. By treating international trade as a winner-takes-all, zero-sum game in which the US makes its own rules, the Trump administration has weakened the incentive for countries to engage in the kind of policy co-operation that has been a hallmark of the international economic order since World War II. Why should China bow to a US that treats it as an economic enemy?

To be sure, it remains unclear whether the US Treasury has advanced the kind of formal proceedings – which normally involve the International Monetary Fund – against China that would usually follow official accusations of currency manipulation. And the Trump administration has a track record of making big threats and then backing away – while claiming credit for averting disaster.

By escalating tensions and fuelling uncertainty, however, Trump’s reckless posturing can have serious consequences, even if he does not follow through. At a time when the global economy is slowing down, this is a risk nobody should be willing to take.

Paola Subacchi is professor of international economics at Queen Mary Global Policy Institute, Queen Mary University of London and author of The People’s Money: How China is Building a Global Currency.