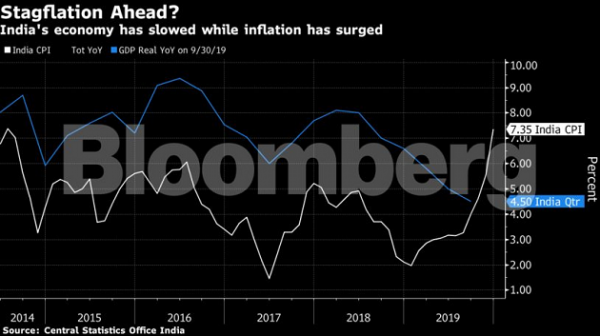

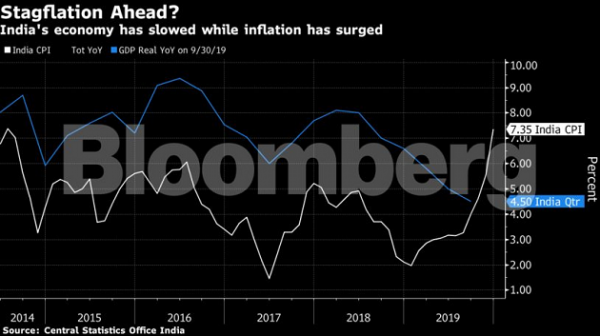

Just two years ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was helming an economy expanding 8%, spurring optimism India was on a path to become a major global growth driver. Now, stagflation looms as the economy grinds toward its slowest expansion in more than a decade and inflation spikes above the central bank’s target, driven by higher food prices. Social unrest against a restrictive new citizenship law is yet another challenge.

And there’s few good options to deal with the slowdown. Dwindling government revenue and an already-stretched budget limit scope for fiscal support, while the shock 7.35% surge in inflation in December and the threat of higher oil prices mean the door for further interest rate cuts is closing.

So what went wrong? At the heart of India’s problems is a slump in consumption following a combination of policy missteps, from the unprecedented decision to ban high-value cash notes at the end of 2016, to the chaotic implementation of a unified goods and services tax the following year. That was followed shortly after by a credit crunch, which triggered a crisis among shadow lenders – a key provider of small loans to hundreds of millions of consumers and businesses.

Volatile Oil

Consumption makes up about 60% of gross domestic product, and spending has slumped as businesses shed jobs and put off investment plans. Consumer sentiment remains in the doldrums and the recent volatility in oil prices could be a further drag on spending. Economic growth in the fiscal year through March 31 is set to slow to an estimated 5%, the weakest pace in more than a decade. “The recovery is likely to be very gradual and a stagflation scenario is likely,” said Teresa John, an economist at Nirmal Bang Equities Pvt in Mumbai.

The central bank’s five interest-rate cuts last year and billions of dollars of liquidity pumped into financial markets have done little to spur lending. That’s because banks are already saddled with one of the worst stressed-asset ratios in the world and are neither lending much nor transmitting rate cuts to borrowers.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

India’s recovery is still sputtering. Our GDP tracker shows growth slamming into reverse in November after a pickup in October, adjusted for year-earlier base effects. This cautions against any premature withdrawal of policy support. Our view is that the government and the central bank need to step up stimulus.

The government has taken steps to revive the economy, but they aren’t bearing fruit yet. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman gave companies $20 billion worth of tax cuts, merged weak state-run banks with stronger ones and eased foreign investment rules. The government will also sell state assets in its biggest privatization drive in more than a decade.

“We are really extremely close to a point where we could be dipping into a major recession,” Abhijit Banerjee, winner of the Nobel prize for economics last year, said this month in Mumbai. “The critical problem in the Indian economy is demand. You definitely want to stimulate demand,” he said, urging authorities to abandon their inflation and budget deficit targets.

There are some early signs that the economy may be bottoming out. The latest high-frequency indicators, such as the purchasing managers indexes for manufacturing and services, show activity is picking up. Industrial production and capital expenditure also improved late last year.

Economists are forecasting a rebound in growth to 6.2% in the fiscal year through March 2021, although much will depend on how quickly global demand and domestic spending recovers.

Nouriel Roubini, a New York University professor and well-known economic doomsayer, told delegates at a Mumbai conference last week that he doesn’t see evidence yet that the “slowdown is going to give way to a significant pick-up in growth in this financial year.” He added that policy makers’ attention “should have been concentrated on the economy and is instead distracted by political things.”

Commenting feature is disabled in your country/region.