We can do it! Photo: Margaret Bourke-White/The LIFE Picture Collection via

The American economy is an unnatural disaster. Four decades of upward redistribution — followed by seven months of criminally negligent pandemic management — have left the U.S. facing mass small-business bankruptcies, a burgeoning eviction crisis, widespread unemployment, and historic inequality. Absent dramatic economic reforms, neo-feudalism will be our nation’s true Manifest Destiny.

The global climate has become a man-made menace. Decades of heedless carbon-burning and political myopia have condemned humanity to an increasingly inhospitable planet. We’ve already bought ourselves a generation of rising temperatures, raging wildfires, flooded coastlines, and devastating droughts. Without a rapid transition to a non-carbon economy, the moral arc of history may bend toward water wars.

For a long time, policy-makers have posited a hard trade-off between tackling the crisis of economic stagnation and that of ecological decline. After all, carbon emissions rose in tandem with living standards, and cheap fossil energy was the literal fuel of postwar prosperity. Further, while a state-led effort to rapidly reorganize the U.S. economy around sustainable production might succeed in slowing planetary warming, economic orthodoxy insisted that it would certainly slow growth: Large-scale public spending on renewables would crowd out private investment. The real resources and labor required for a continent-spanning green infrastructure program would exhaust our economy’s productive capacity, forcing either the suppression of consumer spending or spiraling inflation. And anyhow, the public sector would surely misallocate a hefty percentage of the resources it commandeered; as Larry Summers once warned, “The government is a crappy venture capitalist.”

In recent years, however, a growing appreciation of climate change’s material toll, combined with mounting evidence of a global shortfall in aggregate demand, have lowered the contradictions between climate and economic policy. At a time when the private sector is failing to make use of millions of workers and idle capital — and deflation is a bigger threat than inflation — massive public investment to remake America’s infrastructure, vehicle fleets, and energy industry looks like a recipe for reviving shared prosperity and achieving climate sustainability. It’s this “kill two birds with one wind turbine” logic that undergirds Joe Biden’s $2 trillion green-stimulus proposal.

And yet: If economic orthodoxy is less hostile to climate action than it once was, it still serves as an obstacle to reforms commensurate with the scale of the ecological problem. The Biden team itself oscillates between advocating for a mini–Green New Deal and wringing its hands about the national debt. Despite the failure of unprecedented deficit spending to produce significant inflation, Biden advisers have warned that — thanks to Trump’s tax cuts — the fiscal “pantry is going to be bare.” Meanwhile, the candidate himself has said Trump’s policies have “eaten a lot of our seed corn.” In other words: It appears that the Democratic nominee believes that — independent of political constraints — there are hard limits on how much the public sector can spend on climate before its efforts become a drag on economic prosperity.

If so, Biden would be well advised to read the Roosevelt Institute’s new analysis of America’s World War II economy.

The analogy between the economic mobilization that America mounted to take on the Nazis and the one that it should mount to beat back climate change is flawed in many respects. To name just one: The former did not pose remotely as large a threat to incumbent U.S. industries as the latter does. Nevertheless, if we wish to anticipate how a massive, state-directed economic mobilization against climate change would impact growth, inflation, and inequality, there is no better precedent than FDR’s war economy.

And, as economists J.W. Mason and Andrew Bossie argue in the Roosevelt Institute’s report, this precedent is an encouraging one.

One cornerstone of conventional macroeconomics is that an economy’s productive potential is determined by “structural factors,” like existing technology and demographics — not by changes in demand for goods and services. Thus, during a recession, deficit spending can help expedite an economy’s return to its previous growth trajectory, but such stimulus has no impact on the economy’s long-run growth potential.

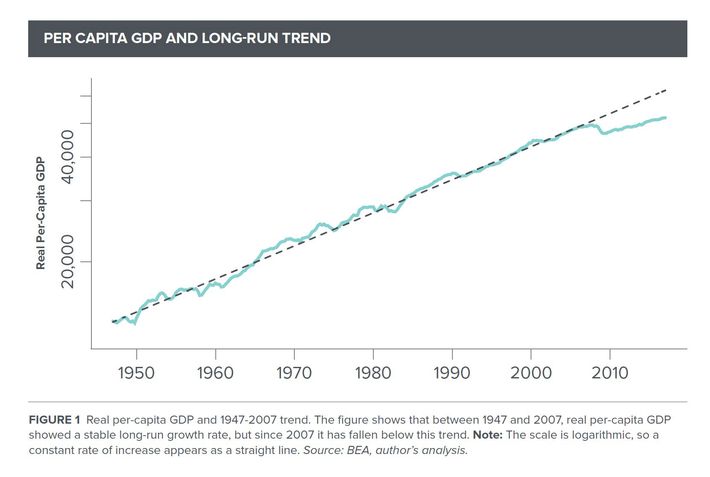

The Great Recession badly undermined this theory. The extended period of mass unemployment that followed the 2008 crash durably reduced the U.S. economy’s productive capacity by, among other things, causing many discouraged workers to exit the labor force. In hindsight, had the public sector provided a more robust fiscal stimulus in 2009, it would not only have mitigated material hardship but also averted a reduction in the supply of workers and thus increased the U.S. economy’s long-run growth prospects. As is, America never caught back up to its pre-2008 growth trajectory.

Mason and Bossie show that the exceptional public spending of the World War II era triggered a converse phenomenon. Between soldiers and civilian personnel, the war effort employed about 13 million workers — without reducing the size of the nonagricultural civilian labor force. In other words: The demand created by the anti-Axis mobilization generated a larger supply of laborers. Eight million Americans who had previously not been seeking work (and had not been numbered among the officially “unemployed”) were drawn into the labor market by the opportunities the war boom afforded (many, but not all, of these workers were women). Meanwhile, nearly 1 million other workers were drawn out of the agricultural sector, where they were apparently not much needed. In other words: Public spending simultaneously increased the size of the U.S. labor force and accelerated the redeployment of agricultural workers to higher productivity sectors.

Relatedly, the wartime mobilization accelerated technological innovation and productivity growth. In the decades preceding the conflict, America saw an average annual increase in total-factor productivity of less than one percent; during the war, that climbed to an average of 3.5 percent. In the war industries — which is to say, in the parts of the economy most influenced by state investment and planning — productivity gains were often larger. In 1942, it took an average of 3.2 worker hours to produce a pound of airframe; by 1945, it took only 0.47 worker hours.

Why did this period of exceptionally statist economic policy yield exceptionally high rates of innovation, in defiance of conservative economic teaching? One reason is that conventional economic models often assume a world of decreasing returns: Which is to say, a world in which every unit produced costs more than the last one, as the inputs required to make it grow more scarce and therefore costly to secure. Although this dynamic may prevail in certain industries, the opposite is more broadly true: Producing the first unit of a new product or technology is immensely expensive (and unprofitable) but gets cheaper from there. And this dynamic means that there are many potential, productivity-enhancing innovations that the private sector is liable to ignore if left to its own devices. As Mason and Bossie explain:

When wind power or solar photovoltaic technology were getting started, producing them was prohibitively expensive — just like the first runs of aircraft in the 1940s. Only a period of producing at a loss would allow for the experimentation and learning-by-doing that would eventually allow them to be commercially viable. But private business is rarely willing or able to shoulder the necessary losses to get over the hump — especially since the gains, when they come, will be broadly shared … In economists’ terms, an increasing-returns world is one with multiple equilibria — an industry may not exist at all, or may exist at a large scale, but there is no viable position in between. In a world like this, public sector leadership is needed to get across the gap.

Critically, by increasing the supply of workers — and their collective productivity per hour — the wartime mobilization allowed Americans to have their guns and (figurative) butter too: Even as much of economic production was devoted to shipping bombs and planes across the pond, civilian living standards actually rose during the war. Yes, rationing of consumer goods was common during wartime. But this was not because the overall stock of consumer products declined; it was because workers’ wages went up, thereby increasing demand for such products. Overall, private consumption rose every year of the war except for 1942. And rationing ultimately functioned less as forced austerity than forced savings: With consumption opportunities limited, U.S. households built up savings that would later facilitate the postwar boom and formation of a broad-based middle class.

Graphic: Roosevelt Institute

Finally, although the explosion in public spending during the war did produce a rise in inflation, this was less a product of excessively high economywide demand than of bottlenecks in specific sectors. Thus, policy-makers were able to keep inflation in check through targeted price controls and investment — without reducing overall demand by engineering a recession (which has been our government’s go-to method for combating inflation since the late 1970s).

The upshot of all of this for the Green New Deal is fairly straightforward. Between 1940 and 1945, the U.S. government managed to increase military spending by an amount equal to 70 percent of 1940 GDP — while increasing productivity and technological innovation, raising civilian living standards, laying the groundwork for a decades-long postwar boom, and avoiding runaway inflation. Obviously, there are a great number of distinctions between the macroeconomic conditions of 1940 and those of 2020. But 70 percent of last year’s U.S. GDP would amount to roughly $15 trillion. If we could figure out how to execute public spending and planning on that scale 80 years ago, we can presumably execute it at a fraction of that scale (say, $5 trillion over five years?) today.

What’s more, if we did find the political will to mount a massive green industrial policy — which, along with the private sector’s ordinary activities, enlisted all available workers and capital — we would not only make great progress on our climate problem but on our inequality problem as well. Or so historical experience would suggest.

As Mason and Bossie note, the mobilization for World War II coincided with the greatest compression of incomes in U.S. history, with the top one percent’s share of national income falling by a third. Meanwhile, wage gains among workers were largest in the industries that had the lowest compensation rates before the war. This great class leveling had profound implications for racial inequality. In an economy where unemployment was virtually abolished, businesses had less room to discriminate: At the war’s start, the median wage for a Black man in the U.S. was equal to 35 percent of a similarly aged white man; by the war’s end, it reached 50 percent. The U.S. labor market has never been as tight as it was during World War II — and there has been roughly zero convergence between the median wages of Black and white men since Japan surrendered. In fact, this racial wage gap was higher in 2010 than it had been in 1950.

Graphic: Roosevelt Institute

The “green dream (or whatever)” is thus eminently realizable. We can have the public sector direct trillions of dollars’ worth of capital and labor toward building a sustainable economy while increasing growth, innovation, and consumer living standards (there may be Malthusian limits to certain kinds of consumption, but not to growth of consumption in general, since the latter can encompass a wide range of ecologically undemanding services). And we can do all of this while reducing class- and race-based inequities; in fact, a reduction in such inequities would likely be an automatic by-product of running the economy at full capacity.

There is no conflict between climate mitigation and economic growth, only between the interests of reactionary plutocrats and those of the general public. If Biden truly wishes to mount an “FDR-size presidency,” he’ll welcome the former’s hatred.

Feeling Hopeless About Climate? Just Remember World War II.

THE FEED

the city politic

Corey Johnson on Why He’s Dropping Out of the New York City Mayoral Race

By David Freedlander

“I was maybe not feeling my best self,” said the City Council Speaker. “But I felt like I couldn’t really acknowledge that.”

politics

Trump Booed During Visit to Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Casket

By Matt Stieb

The crowd at the viewing for the late Supreme Court justice did not respond well to the presence of a president who questioned her reported last wish.

the national interest

Trump Finally Releases Fake ‘Plan’ to Protect Preexisting Conditions

By Jonathan Chait

We’ve been waiting “two weeks” for almost four years.

vision 2020

Pompeo’s Swing-State Appearances Look a Lot Like Campaigning for Trump

By Charlotte Klein

The secretary of State has been touting the president’s agenda in key battlegrounds, violating norms and possibly the Hatch Act.

donald trump

I Don’t Know Where This Ends. But I Cannot Stop Panicking About November.

By Jerry Saltz

Last night my wife and I were lying in bed. One of us said, “What if we lose?” Immediately, anxiety completely overwhelmed us.

ron desantis

Ron DeSantis Is Risking Floridians’ Lives to Benefit Trump

By Zak Cheney-Rice

The governor’s sycophantic Trump relationship led to disastrous COVID outcomes, and now he’s pushing looser penalties for drivers who kill protesters.

after rbg

American Women Need a Revolution. It Has to Be Bigger Than RBG.

By Sarah Jones

Ruth Bader Ginsburg wasn’t the feminist hero I wanted her to be. If we’re to survive the coming battles, we must be honest about her legacy.

the top line

Why Do Voters Seem to Be Giving Trump a Pass on the Economy?

By Josh Barro

It’s the best thing the president has going for him right now, according to polls — even though it’s a total mess.

Just release a list of the retired senior officials who aren’t backing Biden

Nearly 500 retired senior military officers, as well as former Cabinet secretaries, service chiefs and other officials, have signed an open letter in support of former vice president Joe Biden, the Democratic presidential nominee, saying that he has “the character, principles, wisdom and leadership necessary to address a world on fire.”

The letter, published Thursday morning by National Security Leaders for Biden, is the latest in a series of calls for President Trump’s defeat in the November election.

“We are former public servants who have devoted our careers, and in many cases risked our lives, for the United States,” it says. “We are generals, admirals, senior noncommissioned officers, ambassadors and senior civilian national security leaders. We are Republicans and Democrats, and Independents. We love our country.

“Unfortunately, we also fear for it.”

The letter has been signed by 489 people.

vision 2020

GOP Offers Mild Pushback on Trump’s Threat to ‘Get Rid of the Ballots’

By Benjamin Hart

It’s slightly better than nothing.

religion

Why Being Catholic Isn’t Special in Politics Anymore

By Ed Kilgore

Joe Biden isn’t appealing to Catholic tradition in his bid to become the second Catholic president. But that’s the American way.

climate

The Economy of World War II Proved a Green New Deal Is Possible

By Eric Levitz

Americans didn’t have to choose between guns and butter during the war. And they don’t need to choose between prosperity and sustainability today.

black lives matter

Renewed Unrest After Officers in Breonna Taylor Case Cleared of Criminal Charges

By Matt Stieb

Two police officers have reportedly been shot in Louisville, where the officers who killed Breonna Taylor were cleared of criminal charges.

the national interest

Trump: ‘Get Rid of the Ballots … There Won’t Be a Transfer’ of Power

By Jonathan Chait

Trump, once again, did not commit to accepting the election results, and suggested throwing out mail ballots to ensure a “continuation” of power.

electric vehicles

California to Ban Sales of New Gas-Powered Cars in 2035

By Matt Stieb

Governor Newsom’s office estimates the rule will cut the state’s greenhouse-gas emissions by 35 percent and nitrogen oxide emissions by 80 percent.

supreme court

Trump Says Supreme Court Needs 9 Justices for Potential Election Dispute

By Matt Stieb

Meanwhile, Republicans at the state and national level are reportedly gaming out ways to dispute the election.

the national interest

Republican Report Suggests Hunter Biden, Donald Trump Both Unfit for Office

By Jonathan Chait

The one person who comes out of the Ukraine scandal looking good? Joe Biden.

vision 2020

A Nightmarish End to the 2020 Elections Is Becoming All Too Plausible

By Ed Kilgore

Barton Gellman lays out in great detail how Trump might use chaos to steal a second term, or at least create a constitutional crisis.

power

Only One Officer Was Charged in Breonna Taylor’s Killing

By Bridget Read

Brett Hankison has been charged with wanton endangerment, but the other two officers will face no charges.

the national interest

Report: Trump, a Giant Racist, Said Jews Are ‘Only in It for Themselves’

By Jonathan Chait

The president continues to provide evidence of his massive racism.

congress

Stopgap Spending Deal Ends Government Shutdown Threat

By Ed Kilgore

Pelosi gave in on farm aid Trump is distributing in exchange for some concessions, relegating spending disputes to a lame-duck session.

covid-19

Johnson & Johnson’s Single-Shot COVID-19 Vaccine Moves to Final Trial Stage

By Benjamin Hart

The company says it could determine whether the dose is effective by the end of this year.

The latest COVID-19 vaccine to enter the final stage of trials is easier to store and administer

The first coronavirus vaccine that aims to protect people with a single shot has entered the final stages of testing in the United States in an international trial that will recruit up to 60,000 participants.

The experimental vaccine being developed by pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson is the fourth vaccine to enter the large, Phase 3 trials in the United States that will determine whether they are effective and safe. Paul Stoffels, chief scientific officer of J&J, predicted that there may be enough data to have results by the end of the year and said the company plans to manufacture 1 billion doses next year.

Three other vaccine candidates have a head start, with U.S. trials that began earlier in the summer, but the vaccine being developed by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, a division of J&J, has several advantages that could make it logistically easier to administer and distribute if it is proved safe and effective.

The company is initially testing a single dose, whereas the other vaccines being tested in the United States require a return visit and second shot three to four weeks after the first one to trigger a protective immune response. The J&J vaccine can also be stored in liquid form at refrigerator temperatures for three months, whereas two of the front-runner candidates must be frozen or kept at ultracold temperatures for long-term storage.

Already a subscriber? Log in or link your magazine subscription