Advertisement

NEWS ANALYSIS

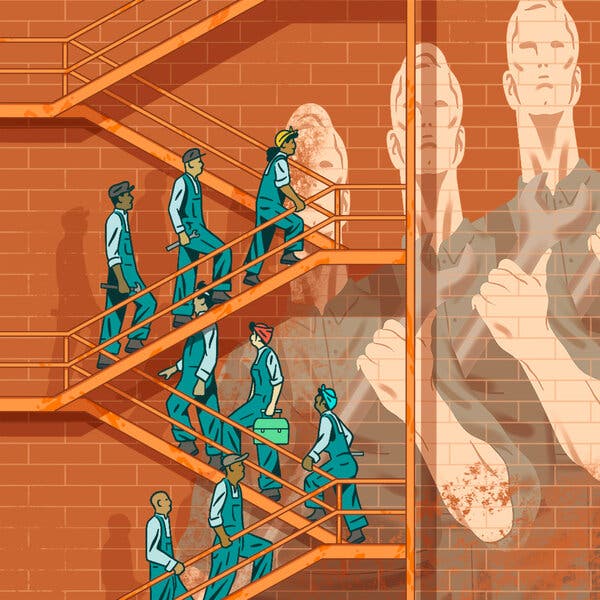

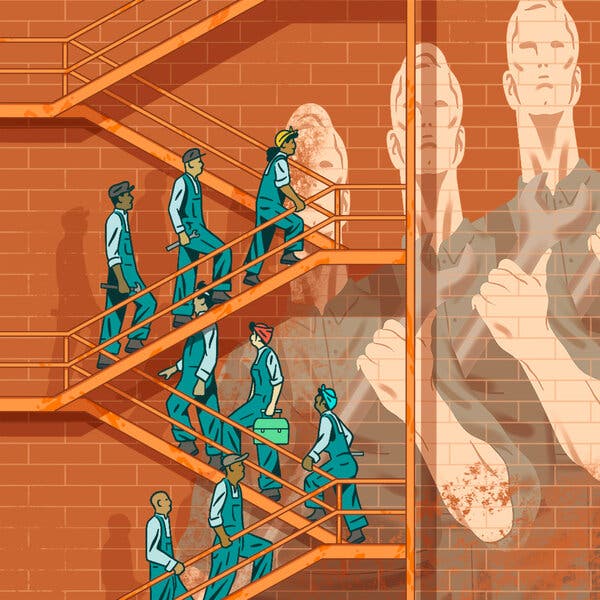

How expanding opportunity for women, immigrants and nonwhite workers helped everyone — and why we need to do so again.

Mr. Tankersley covers economic policy in the Washington bureau of The Times.

The United States long reserved its most lucrative occupations for an elite class of white men. Those men held power by selling everyone else a myth: The biggest threat to workers like you are workers who do not look like you. Again and again, they told working-class white men that they were losing out on good jobs to women, nonwhite men and immigrants.

It was, and remains, a politically potent lie. It is undercut by the real story of how America engineered its Golden Era of shared prosperity — the great middle-class expansion in the decades after World War II.

Americans deserve to know the truth about that Golden Era, which was not the whitewashed, “Leave It to Beaver” tale that so many people have been led to believe. They deserve to know who built the middle class and can actually rebuild it, for all workers, no matter their race or gender or hometown.

We need to hear it now, as our nation is immersed in a pandemic recession and a summer of protests demanding equality, and as American workers struggle to shake off decades of sluggish wage growth. We need to hear it because it is a beacon of hope in a bleak time for our economy, but more important because the lies that elite white men peddle about workers in conflict have made the economy worse for everyone, for far too long.

The hopeful truth is that when Americans band together to force open the gates of opportunity for women, for Black men, for the groups that have long been oppressed in our economy, everyone gets ahead.

I have spent my career as an economics reporter consumed by the questions of how America might revive the Golden Era of the middle class that boomed after World War II. I have searched for the secret to restoring prosperity for the sons of lumber-mill workers in my home county, where the timber industry crashed in the 1980s, or the burned-out factories along the Ohio River, where I chased politicians in the early 2000s who were promising — and failing — to bring the good jobs back.

The old jobs are not coming back. What I have learned over time is that our best hope to create a new wave of good ones is to invest in the groups of Americans who were responsible for the success of our economy at the time it worked best for working people.

The economy thrived after World War II in large part because America made it easier for people who had been previously shut out of economic opportunity — women, minority groups, immigrants — to enter the work force and climb the economic ladder, to make better use of their talents and potential. In 1960, cutting-edge research from economists at the University of Chicago and Stanford University has documented, more than half of Black men in America worked as janitors, freight handlers or something similar. Only 2 percent of women and Black men worked in what economists call “high-skill” jobs that pay high wages, like engineering or law. Ninety-four percent of doctors in the United States were white men.

That disparity was by design. It protected white male elites. Everyone else was barred entry to top professions by overt discrimination, inequality of schooling, social convention and, often, the law itself. They were devalued as humans and as workers. (Slavery was the greatest devaluation, but the gates of opportunity remained closed to most enslaved Americans and their descendants through Emancipation and its aftermath.)

Women and nonwhite men gradually chipped away at those barriers, in fits and starts. They seized opportunities, like a war effort creating a need for workers to replace the men being sent abroad to fight. They protested and bled and died for civil rights. And when they won victories, it wasn’t just for them, or even for people like them. They generated economic gains that helped everyone.

The Chicago and Stanford economists calculated that the simple, radical act of reducing discrimination against those groups was responsible for more than 40 percent of the country’s per-worker economic growth after 1960. It’s the reason the country could sustain rapid growth with low unemployment, yielding rising wages for everyone, including white men without college degrees.

America’s ruling elites did not learn from that success. The aggressive expansion of opportunity that had driven economic gains was choked off by a backlash to social progress in the 1970s and ’80s. The white men who ran the country declared victory over discrimination far too early, consigning the economy to slower growth. Sustained shared prosperity was replaced by widening inequality, lost jobs and decades of disappointing income growth for workers of all races.

In important ways, much of the work of breaking down discrimination stalled soon after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. “It was fundamentally over by the time of the Reagan presidency,” William A. Darity Jr., a Duke University economist who is one of his profession’s most accomplished researchers on racial discrimination, told me. Over the past several decades, some barriers to advancement for women and nonwhite men have grown back. New ones have grown up beside them.

A host of studies illustrate this. A recent and devastating one is co-authored by a University of Tennessee economic historian, Marianne Wanamaker, who served a year in the White House on President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. She and a co-worker went back to Reconstruction and measured how much easier it was for the sons of poor white men to climb the economic ladder than the sons of poor Black men.

In terms of economic mobility, they found, the penalty for being born Black is the same today as it was in the 1870s.

Women have made more progress in recent decades than Black men, but they are nowhere close to equality. They still earn less for the same work, and they are still blocked by harassment, discrimination and policies from reaching the same heights as white men in many of America’s most important industries.

Take Silicon Valley. In 2018, venture capitalists in the United States distributed $131 billion to start-up businesses, hoping to seed the next Google or Tesla. That money went to nearly 9,000 companies. Just over 2 percent of them were founded entirely by women. Another 12 percent had at least one female founder. The rest, 86 percent, were founded entirely by men.

The statistics show tragedy. They also show opportunity. If America can once again tear down barriers to advancement, it can tap a geyser of entrepreneurship, productivity and talent, which could by itself produce the strong growth and low unemployment that historically drive up wages for the working class, including working-class white men.

If you want to know where the new good jobs will come from — those that will help millions of Americans climb back into the middle class — this is where you should look, to the great untapped talent of America’s women, of its Black men, of the highly skilled immigrants that study after study show to be catalysts of innovation and job creation.

That is not the appeal that populist politicians make to working-class white men, who have been rocked by globalization and automation and the greed of the governing class. But it should be.

All Americans have a stake in the protests for equality they see every night on the news. Working-class white men, like the guys I went to high school with, have a bond with the Black men, the immigrants and the women of all races who have taken to the streets.

The real story of America today is this: If you want to restore the greatness of an economy that doesn’t work for you or your children the way that it used to, those women and men are your best shot at salvation. Their progress will lift you up.

Jim Tankersley covers economic policy in the Washington bureau of The Times. He is the author of “The Riches of This Land: The Untold, True Story of America’s Middle Class,” from which this essay is adapted.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.